Mr. Miyagi:

“Are you ready?

Daniel:

“Yeah, I guess so.”

Mr. Miyagi:

“I guess I must talk.

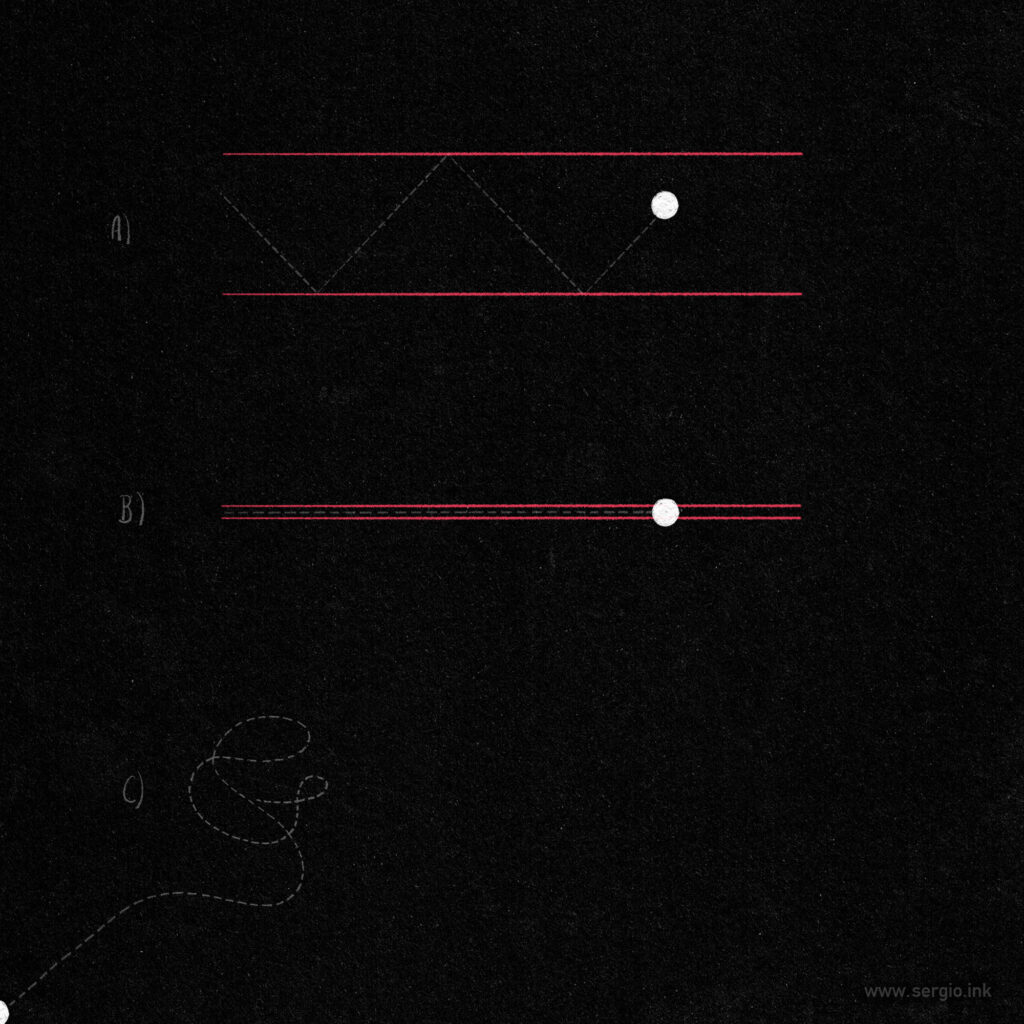

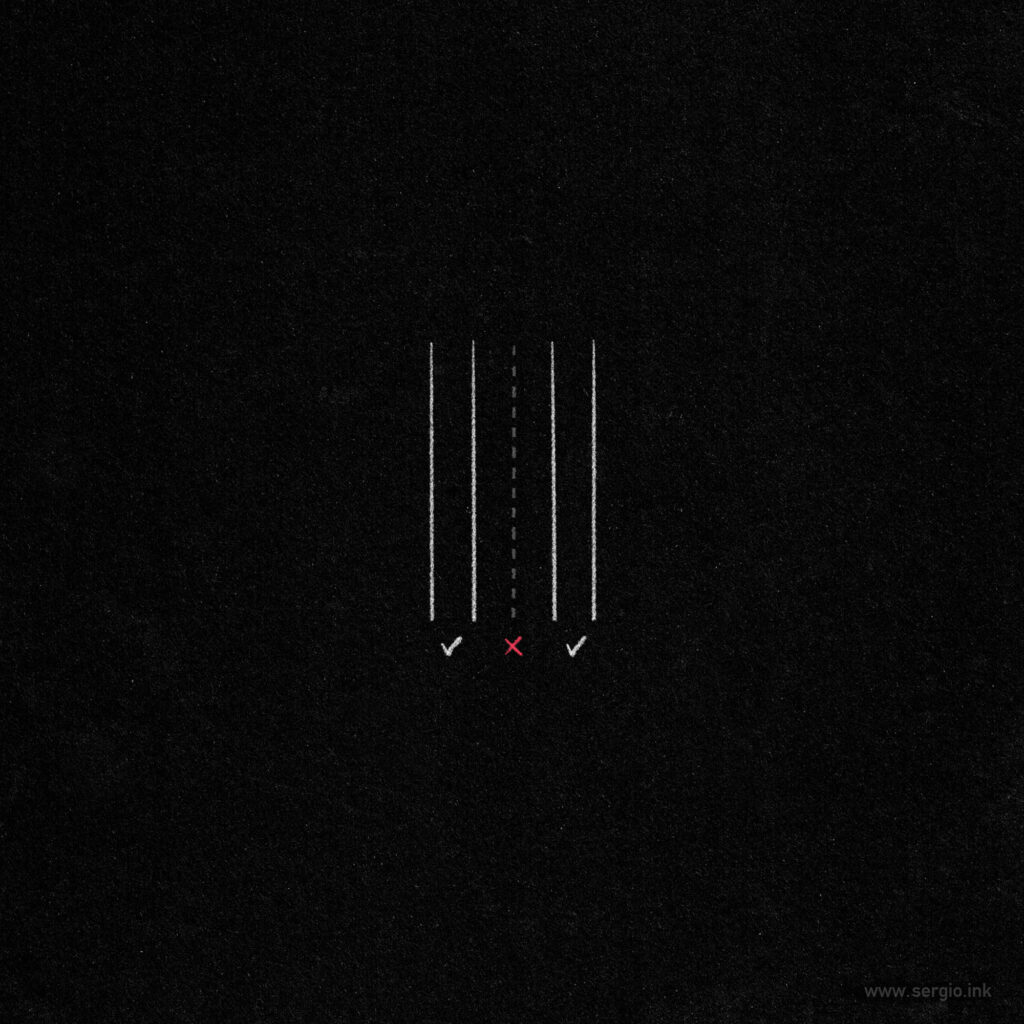

Walk on road.

Walk right side—safe.

Walk left side—safe.

Walk middle—sooner or later, get squish just like grape.

Karate, same thing.

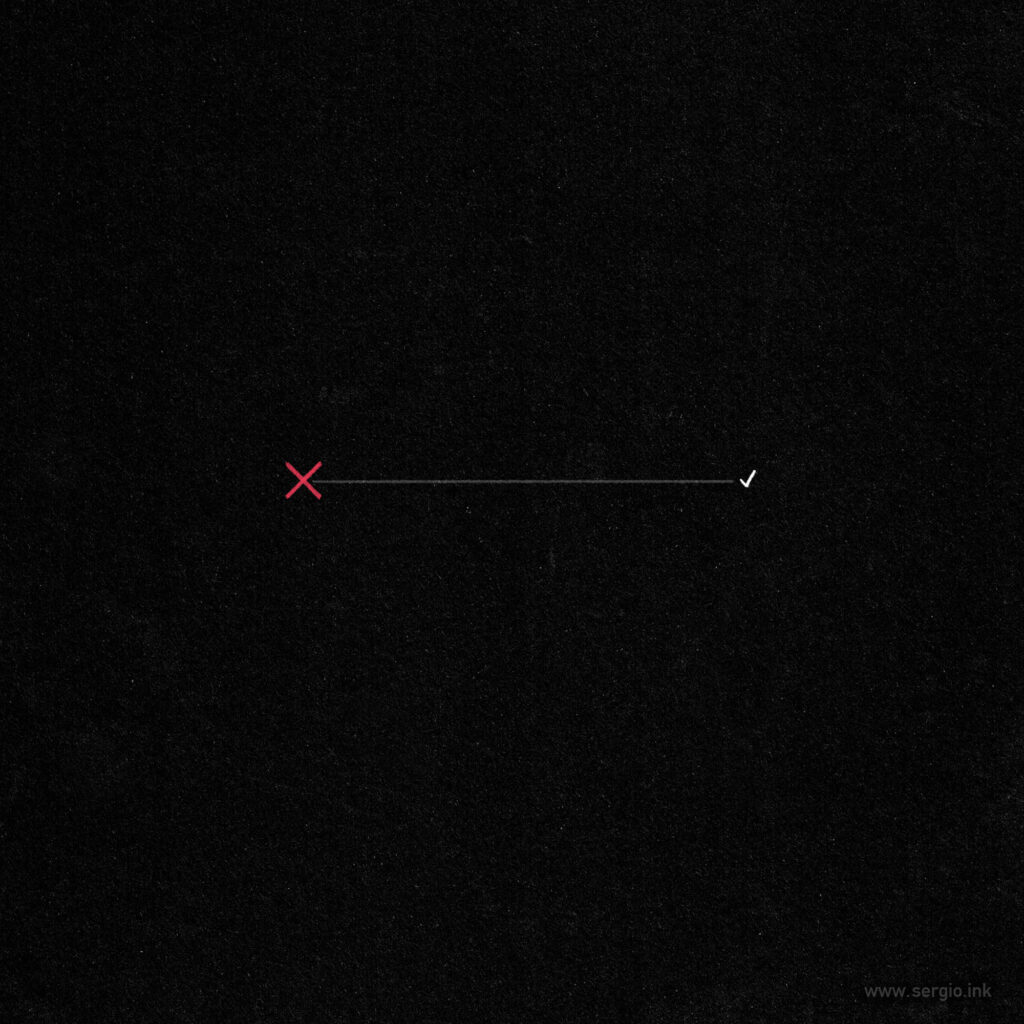

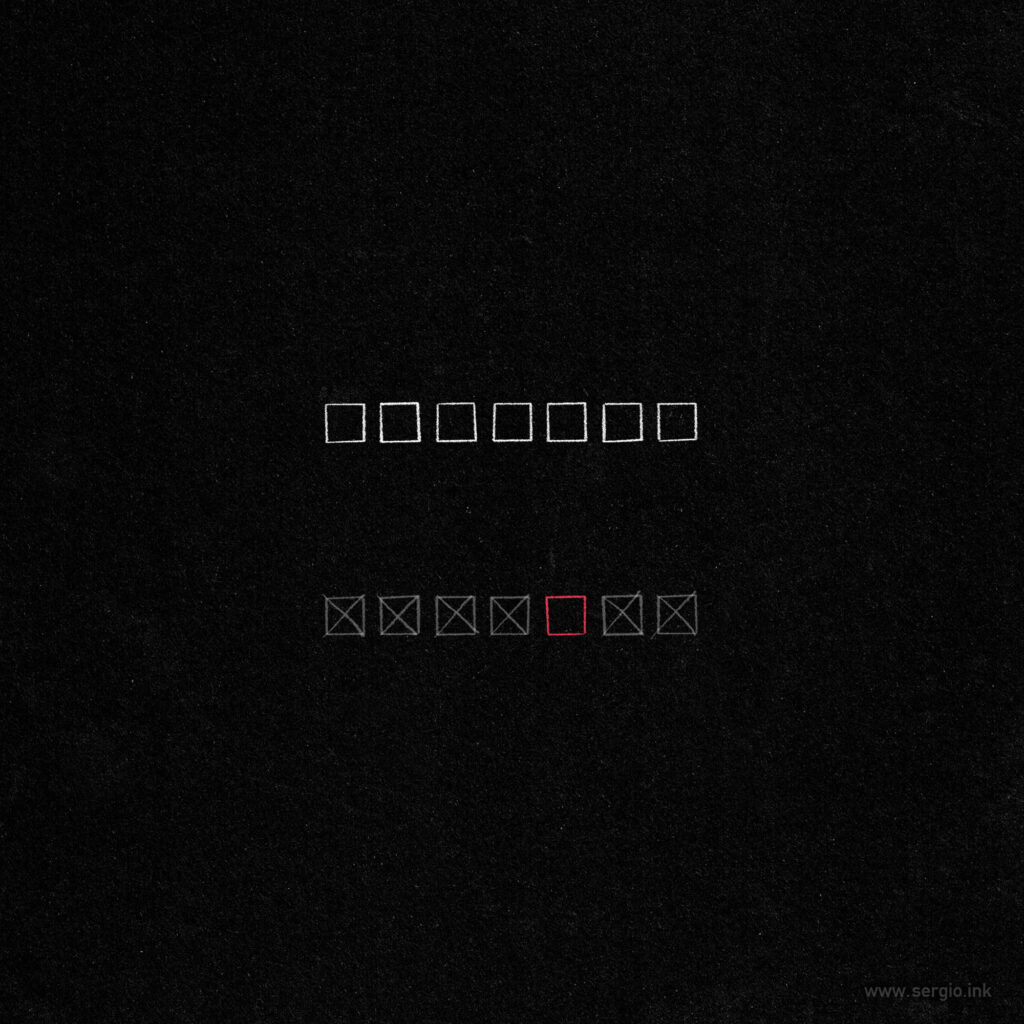

Either you karate do ‘yes,’ or karate do ‘no.’

You karate do ‘guess so’—squish like grape.”

30 years later

It took me three decades to truly understand this valuable message from one of my favorite childhood movies, Karate Kid (1984).

In this scene, Mr. Miyagi appeals to Daniel’s self-awareness by demanding a decision.

Not a lighthearted decision.

Not one made out of youthful naivety.

He demands a conscious and honest one.

The question is:

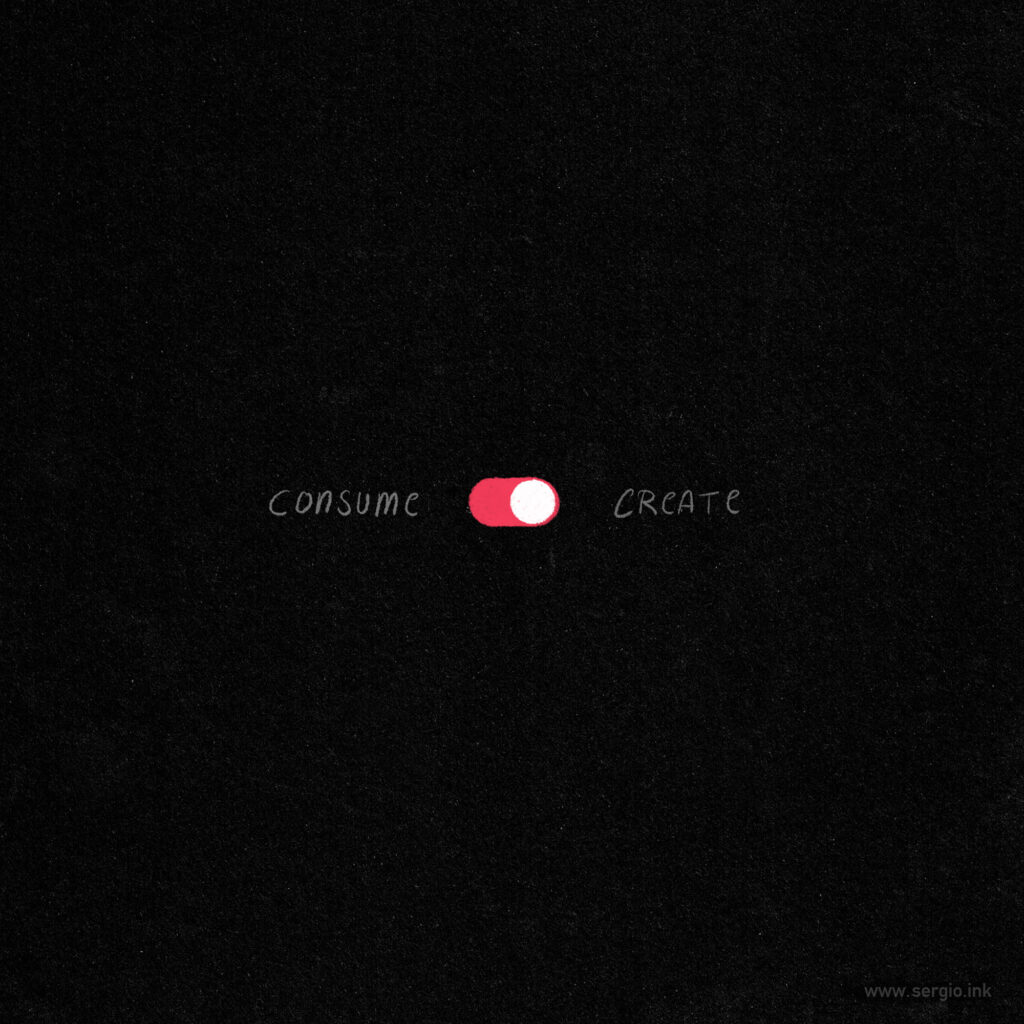

Do or don’t.

Both decisions are valid.

He is not saying “don’t ever quit.”

He is saying, “Whatever your decision is—do it like you mean it.”

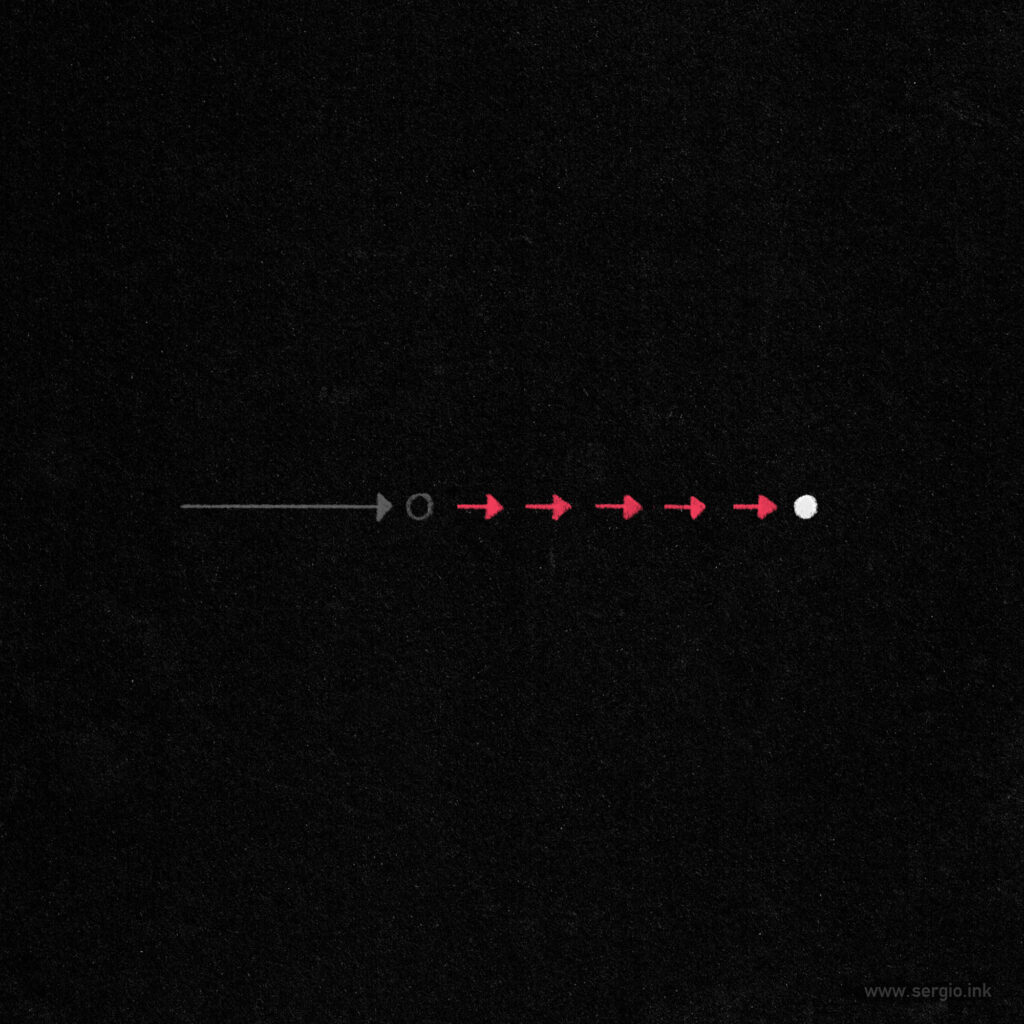

He warns that hesitation, indecision, or half-hearted effort is where danger lives.

The “middle of the road” is where unfinished projects, excuses, blaming, and shattered dreams lie.

Mr. Miyagi talks about 100% commitment—the kind that will inevitably lead to clarity and growth.

I can see why it took me so long to understand. It takes maturity.

And the appreciation of time that young people simply cannot have.

In their perception, time seems to be infinite.

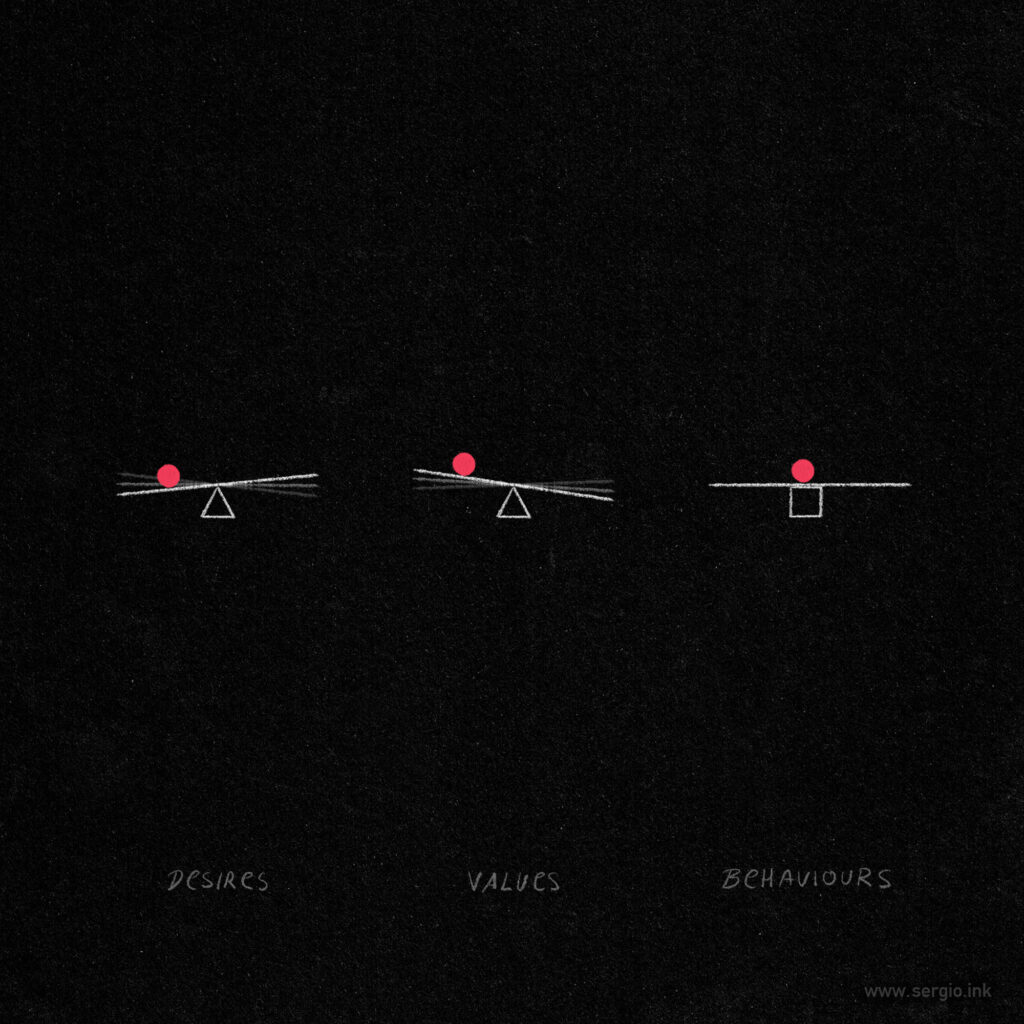

Adults become conscious of their values and limitations.

That’s when we realize:

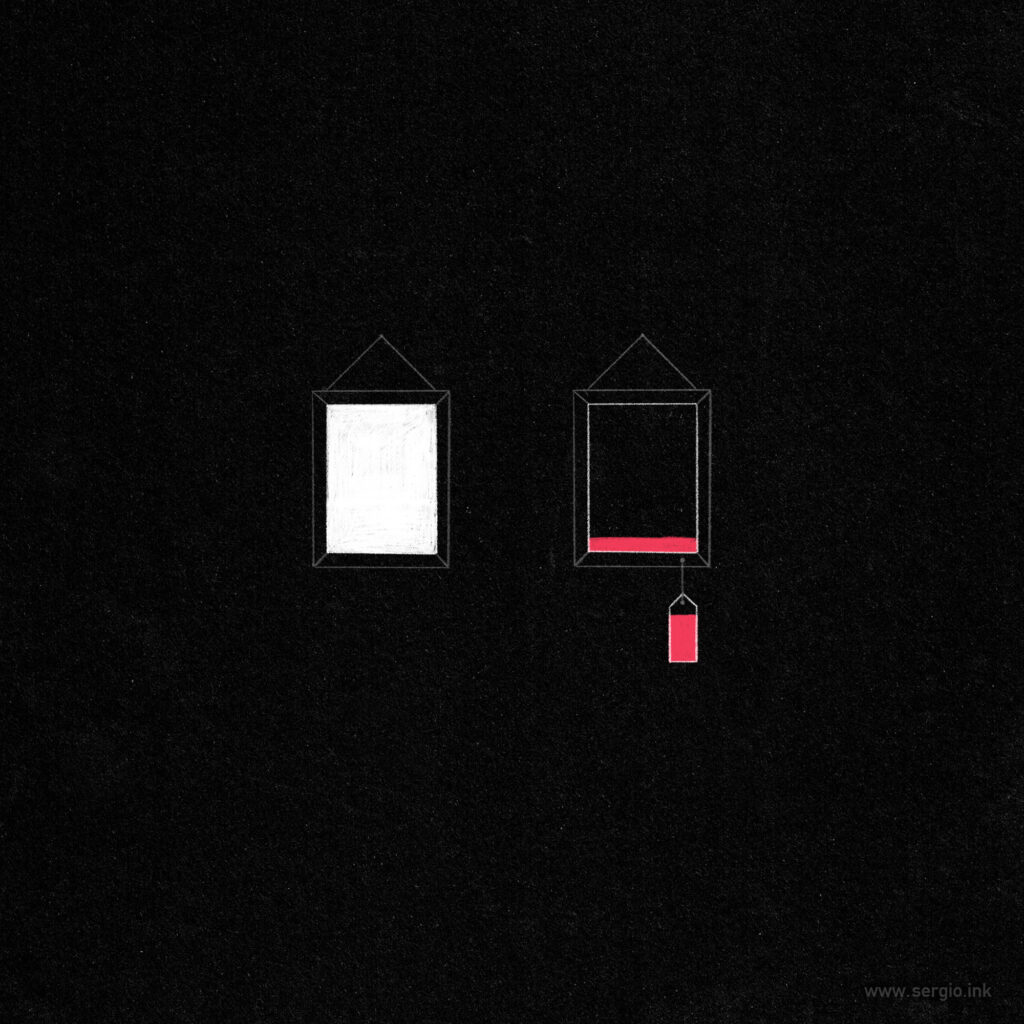

Every “yes” means saying “no” to something else—and vice versa.

The sooner we understand this trade, the sooner we learn to prioritize and dedicate our attention to what truly matters to us.

A Personal Story

At some point, I knew what I wanted to do—become a freelance illustrator. That was my dream, and I decided to turn it into my goal.

I was determined to achieve it.

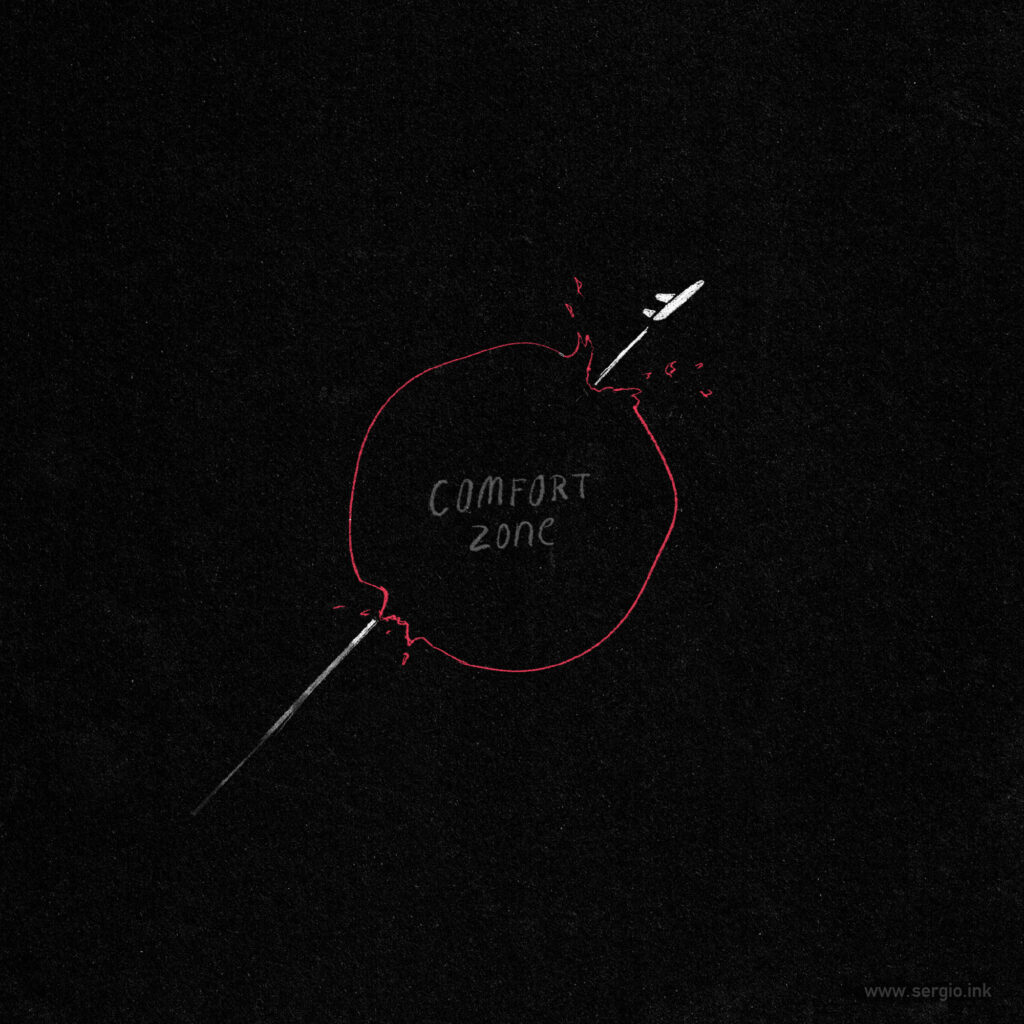

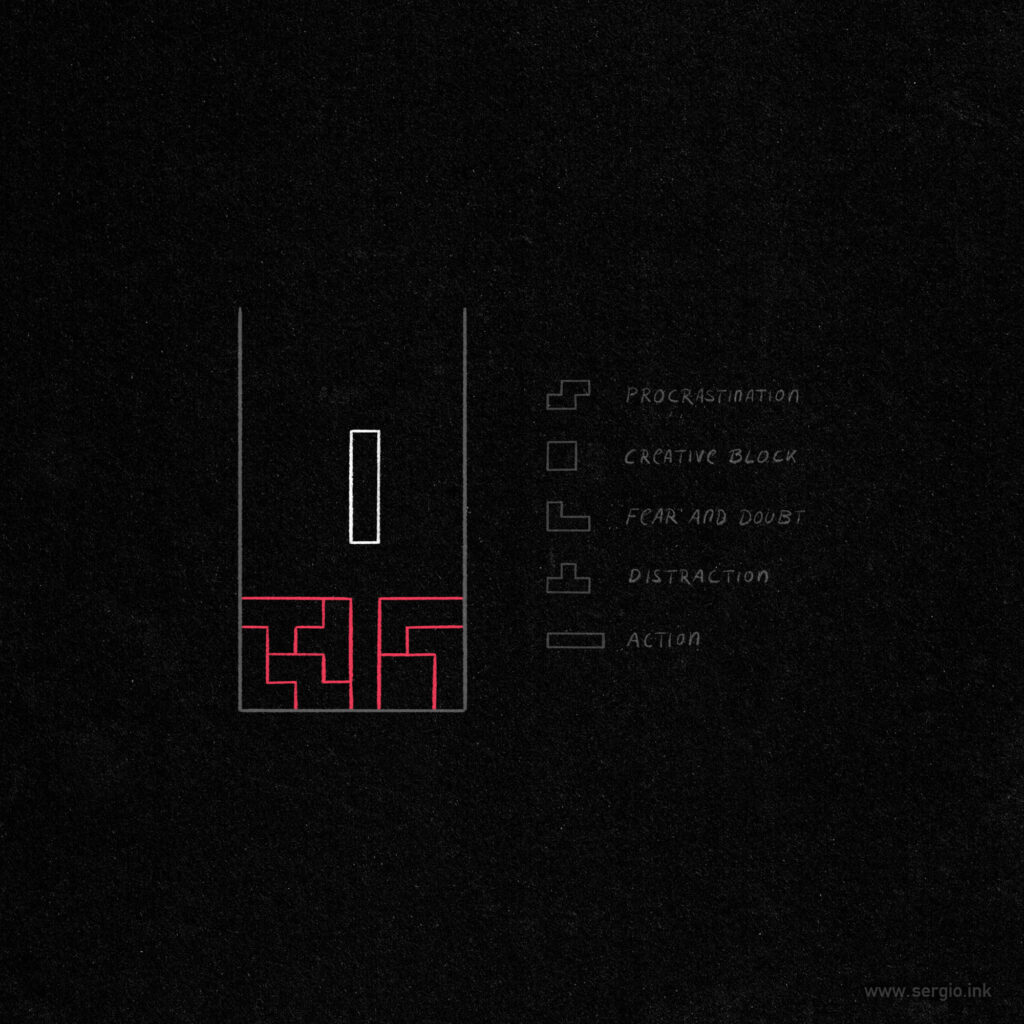

Yet starting your own business comes with fears and doubts.

While working on my illustration portfolio, those insecurities led me to invest time in a plan B—just in case I didn’t succeed.

Plan B was to fall back on the things I used to do in the past—the kind that worked but didn’t fulfill me.

It slowed everything down.

The moment I stepped fully to one side of the road and declined all not-goal-related requests, everything changed—because now I no longer had to trade my time, focus, and determination.

I feel that I made that 100%, non-negotiable commitment Mr. Miyagi talks about.

And after a few months, I started receiving the kind of commissions I had dreamed of.

Starting any life-changing endeavor with commitment is a constant, decision-demanding adventure.

And that‘s the secret to daily excitement and fulfillment.